Hit the Books with Dan Milnor: The Critique

Most people fully invested in the creative life fall in love with their work. This reality comes with an upside and a downside. I believe it’s mandatory to fall in love with my work, but I’ve also been doing this long enough to realize that this same attraction can lead to clouded judgment when it comes to determining whether what I’m making is any good. And this is where I often call in outside help.

Outside help comes in many forms, but let’s back up a minute and think about why knowing what is good and what is not is so critical to growth as an artist. I firmly believe that every generation of creativity only produces a small number of people who truly change the playing field of their chosen industry. In my case, photography.

Every decade or so, someone comes along that makes the rest of us stop and stare. Their work forces us to rethink everything we already know and everything we can only dream about. Knowing who these people are and their achievements allow us to gain context. When we understand this context—and where we fit into it—we can better understand the quality of our own work.

When I work on a project long enough to convince myself it has relevance, I start looking for someone to validate or undermine my beliefs. This is where things start to get real, and where the idea of a critique begins to take shape.

For some, a critique can be a somewhat traumatic experience, knowing the person doing the critique may or may not like the work. For others, the critique, even a harsh resetting of reality, is the only way to move forward.

For those of you who have never subjected your work to a critique, just know that most critiques land somewhere in the middle. There tends to be a sweetness of the getting-to-know-you period, followed by the saltiness of the this-part-could-be-better stage. You might think the salty side would be crushing, but the opposite is true because a critique, in great part, is about trust.

When choosing someone to critique your work, look for someone with real credentials. There is a reason why our industry has full-time picture editors, full-time book designers, and full-time curators, gallerists, and agents. These people spend their entire life immersed in their chosen field. Day after day, they cull from the great herd of creatives. They know the legends and can spot the up-and-comers, and they certainly know their context, which is why their eyes on your work can be so important. When you sit with them, an inherent level of trust is involved, meaning you can trust their opinion based on their experience and expertise.

Several times a year, at least in the photography industry, portfolio reviews are held at various locations across the country. Typically for a small fee, an attendee can have their work critiqued by a range of industry professionals. I look at which location fits my needs, but I also study the list of reviewers and their credentials. And I look for both professionals working in my industry as well as those outside my field. Showing photography to a designer, illustrator, or art museum curator can lead to fresh takes on my work.

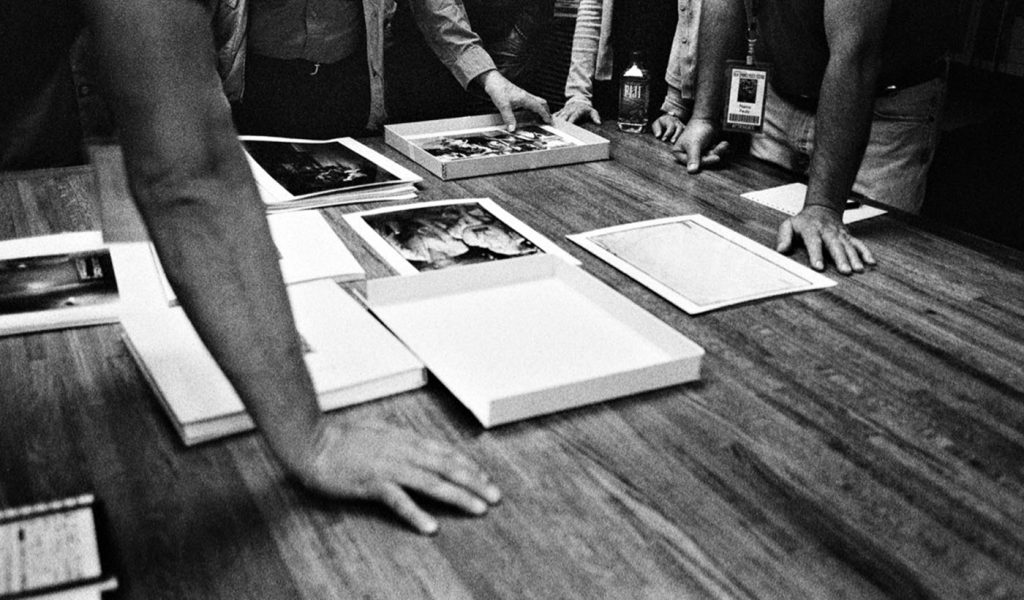

But a critique does far more than just analyze the quality of the work. A critique forces us to edit our work, and I mean truly edit. When you sit with a reviewer, you will have limited time, so if you arrive with 200 pictures in your portfolio, things will not go well. You must edit your work down to only the most significant pieces. Think 20–and realize that a printed portfolio will often resonate more than a laptop or iPad.

A review also forces us to learn how to sequence our work. Which picture or illustration should we show first? What piece should go last?

Finally, a critique also forces us to learn how to speak about our work. This is a hugely important aspect of being a professional creative that often gets overlooked in the feedback process.

Several times a year, I serve as a reviewer (the person giving the critique). Often, attendees will sit down in front of me and immediately open their printed portfolio or laptop and begin showing their work. I always stop them and ask who they are, why they are doing what they are doing, and why I am looking at their work. There needs to be a coherent answer. Think of this as your elevator pitch.

There is a major difference between: “Thank you for asking, I am currently working part-time at a university fundraising department, but my goal is to be a full-time photographer by this time next year, and I’m showing you this work because I’ve worked on this project for 18 months and need to know if I’m missing any major pieces of the story.” And: “Not really sure why I’m here, but it seemed like a cool thing to do.”

Getting your work critiqued is about having your efforts studied by someone who isn’t in love with the work. The reviewer wasn’t there when you made the pictures, designs, or illustrations. Their job is to simply put a critical eye on the work while providing feedback.

Some reviewers will love your work, and others will not. Be prepared for tough love. If someone sees something in your work but knows there is still work to be done, their job is to tell you this straight up. As a friend once said to me before looking at a body of my work, “I’m not your friend right now. I’m your editor. When this is over, I will go back to being your friend.”

Take notes, ask questions, thank your reviewer, and leave them with your contact information. Critiques have led to the discovery of many of the world’s best creatives. With hard work and a little luck, you might be next.