Photography: An Interview with Game-Changer Elliot Ross

The need to make a living means it’s not always easy to stick to your creative guns. But there are a lucky few who manage to follow their own distinctive path to success. Photographer Elliot Ross is one of them. We caught up with him to find out how his unique approach to photography allows him to tell moving stories.

How do you decide what to photograph?

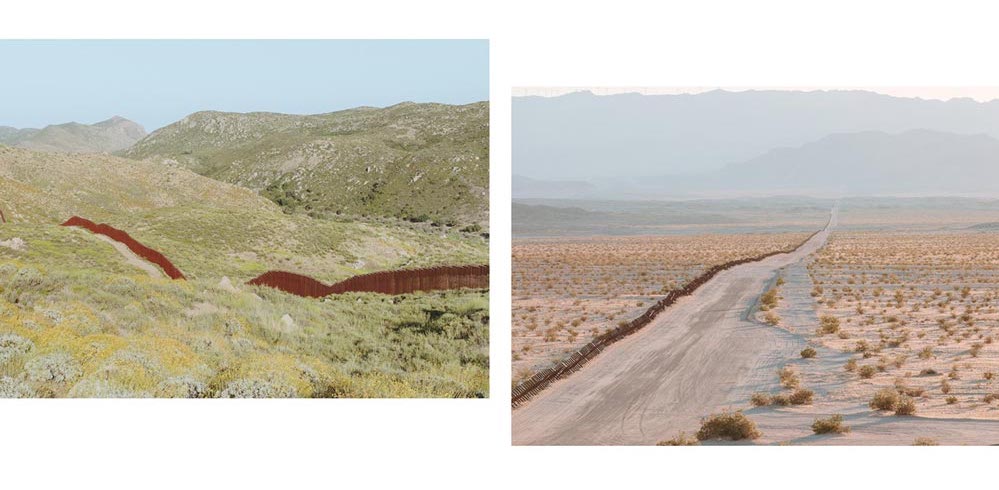

This is perhaps the most challenging and critical step of the entire process of image making and storytelling. Over the years, I’ve narrowed my scope of work into two converging themes: geopolitical borders and geographic isolation. I’m also expanding these ideas to intersect with global climate change. By paying close attention to the type of stories I’m naturally drawn to in wider social discourse, I’ve been able to focus my interests into a much narrower spectrum. Through this concentrated effort, I hope to deepen my understanding of a few key topics, and engender a level of inherent cohesiveness throughout my work.

How would you describe your style and approach to photography?

I think the visual aspect of this question might be better answered by an outside eye, but I’ll do my best with regards to approach. Each idea and step of my process is very intentional. Thorough research is key, as is a defined structure when it comes to production. I find I work most effectively when I have about two thirds of a project concretely laid out, leaving a third for spontaneity and flexibility as the project takes shape and my understanding of its intricacies evolve.

Who or what are your main influences? Who would you consider to be a ‘game-changer’ in the world of photography?

There are countless passive and active influences on my work. Passive influences include where I’m living, what season it is, and the music I’m listening to, among other things. I find my own physical environment and the effects it has on my work fascinating. Manipulating these fundamental, temporal components has great influence over the type of work that results naturally. For this reason, and also to deepen my personal understanding of isolation, I’ve been slowly backing away from my Brooklyn practice and spending longer periods of time in less populated places.

Among my active influences, I’d have to credit first and foremost Joel Sternfeld. I first came across American Prospects in high school. I was taken by the unexpected, ironic, and even whimsical moments he was able to capture with formalist compositional sensibilities. My time working as a photography assistant to Mark Seliger, Martin Schoeller, and Annie Leibovitz also, in retrospect, continues to have a profound impact on how I interact with my subjects and the soft, window light that I’m often attracted to.

In terms of a ‘game-changer’ in the world of photography, the first name that comes to mind is Robert Frank. His work epitomizes the raw reaction to the social consciousness of the beat generation, in a way that no one before or since has been able to achieve.

What would you say the role of photography is in wider society? What purpose does it serve, what impact can it have, and why is it important?

Photography’s power lies in its unique ability to encapsulate an entire concept, issue, or event in a singular, flat plane. The decisive finality in that one frame, when successfully executed, allows someone from any walk of life to identify on a human level with something that would normally go unnoticed. That’s why photography plays a critical role in social discourse. A photograph has, and always will, play a vital role within a democratic society. A photograph can galvanize a movement, provide transparency, reveal an injustice, or stir an empathic response that leads to action.

How has the industry changed over the course of your career as a photographer?

Over the course of my short career, I’ve seen social media change nearly all the rules of the industry. Some words that I find nauseating: content, influencer, creative. These three words have a powerful and profound effect on devaluing our worth as artists. A trend I’ve noticed is companies paying a fraction of the cost for “content” than they did for a “photograph.” Social media threatens artistic practice within photography by cheapening it and making it disposable. That being said, it’s undeniable that this is the new normal. All I can do is avoid using Instagram as a branding tool and instead focus on creating photographs for use in print and point of purchase.

Have books played a role in your photography career?

Using the definition of “book” loosely, the answer is a resounding yes. For the last decade, I’ve kept a regular journal. These artifacts are an amalgam of experiences, daily reflections, news clippings, and polaroids. This practice allows me to digest the day to day while also providing an expanded view, revealing a wider picture of where I’ve come from and where I want to go.

More recently, I’ve begun working with my creative partner and writer, Genevieve Allison, on our first book titled American Backyard. From Brownsville, Texas, to San Diego, California, we drove 10,000 miles, exposing ourselves to nearly every inch of the 2,000-mile U.S. / Mexico border in an effort to understand the real-politiks of the region in the wake of Trump’s election. In what turned into a four-month journey, we tried to look beyond the “border” as a political flashpoint and explore the unique cultural complexion of the borderlands. Through a series of interviews, portraits and topographical studies of both the environment and border infrastructure, we saw a larger, less transparent story to be told about the Southern border. A story of creolization, acculturation, habitat loss, surveillance, and diversity.

After dedicating such a large amount of time towards creating, the process in starting a book is immensely daunting. The costs of creating a book are hard to swallow and, seeing as this is our first time going through this process, I knew it would take more than one try to get things right. So, we turned to Blurb as an inexpensive alternative to experiment with layout and sequencing. I cannot stress how important these print on demand photo books have been throughout this book making process as both a design tool and a marketing prop to garner interest from publishers.

What advice would you give to photographers who aspire to make a living from their craft?

To be successful in photography is to be clear and focused on your intent. For young photographers, and I still consider myself within that camp, it’s okay to not know what you want to say with your work. Experiment heaps, expose yourself to as many passive and active influences as you can and overtime, you’ll begin to notice commonalities in the interests you develop. Nurture these commonalities and focus within your work will grow over time.

Setting a few short-term and long-term goals can help significantly too. They can serve as mile markers in gauging your progress as an artist, as well as a businessperson.

Let me also say that, when starting out, say yes to most everything. I found that the relationships that I made on those low paying jobs that I was on the fence about taking, propelled me on towards a more sustainable income stream down the road.

The last thing I’ll say is that if you want to work for a print magazine or brand, don’t wait for the opportunity to arise—chances are it won’t. Concept idea after idea, narrow those down and then develop and refine. Cold pitches never hurt and it can be surprising what can come from an unsolicited email as long as your ideas are solid, your intent is clear, and you can speak intelligently on the subject.

Thanks Elliot, for such an inspiring and thought provoking interview.

Now it’s your turn. Tell your stories with professional-quality photo books.

This post doesn't have any comment. Be the first one!