Dan Milnor: breaking the rules with layflat paper

Dan Milnor’s photo books are, among many other things, a record of the people, places, and experiences that have shaped his career. Case-in-point is Peru—a strikingly beautiful photo book that doesn’t always stick to the traditional rules of photography. Here he talks to us about the thought process behind his design decisions and why a layflat photo book can help photographers stand out from the crowd.

How does layflat paper work with your kind of content?

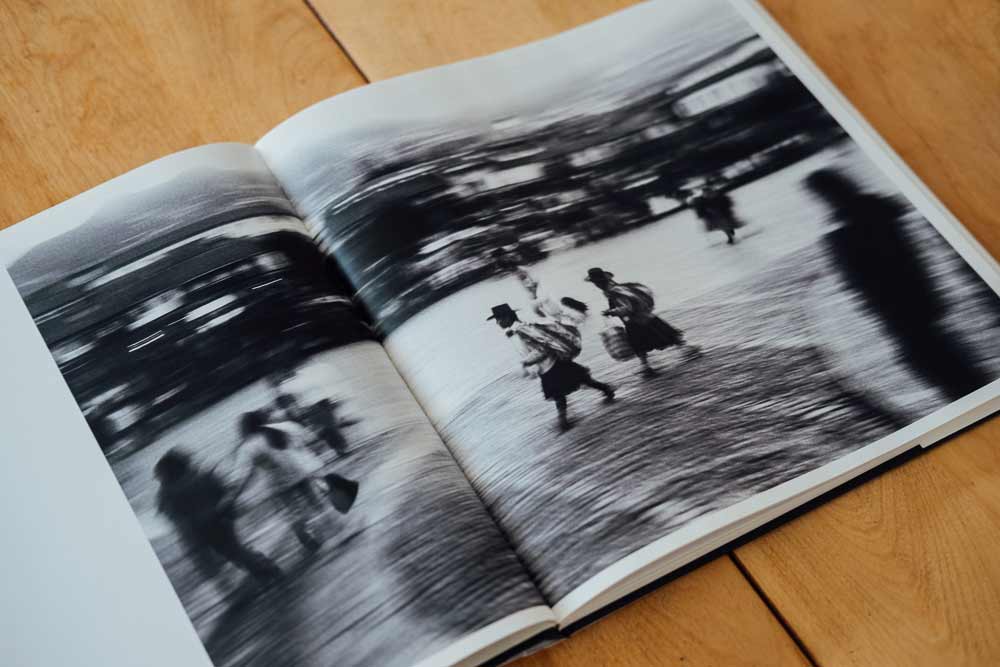

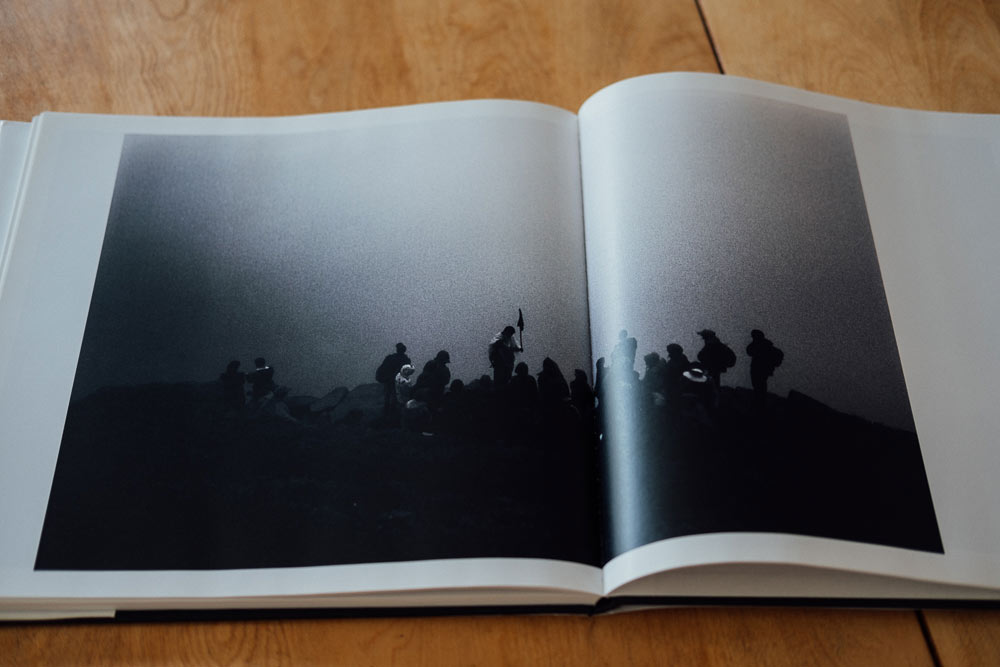

Many of my images are captured in landscape format, so being able to run photographs across the gutter has always been part of my bookmaking. I was always taught that you should never put key elements of an image in the gutter, but I always felt the need to do so. Perhaps it was simply the urge to do what I was told not to, but for me, it always created a sense of visual drama. Now I can do it without losing anything. Layflat paper types allow for the full impact of an image without making the reader bend or pull a book apart to see every inch of it. For a portfolio book, this is a wonderful way to go.

Did using layflat paper offer up any surprises? Did you learn anything new?

I learned that layflat paper is unique. Not only because the pages do, in fact, lay flat, but because it gives books a unique look and feel. Thicker pages make for thicker books, which is all tied to how a reader will view and consume your book. I also learned that I can now run copy across the gutter. This was nearly impossible to do in traditional books and opens up all kinds of new design and layout options.

How did you choose your layouts and decide on the size and format for your book? What factors did you consider?

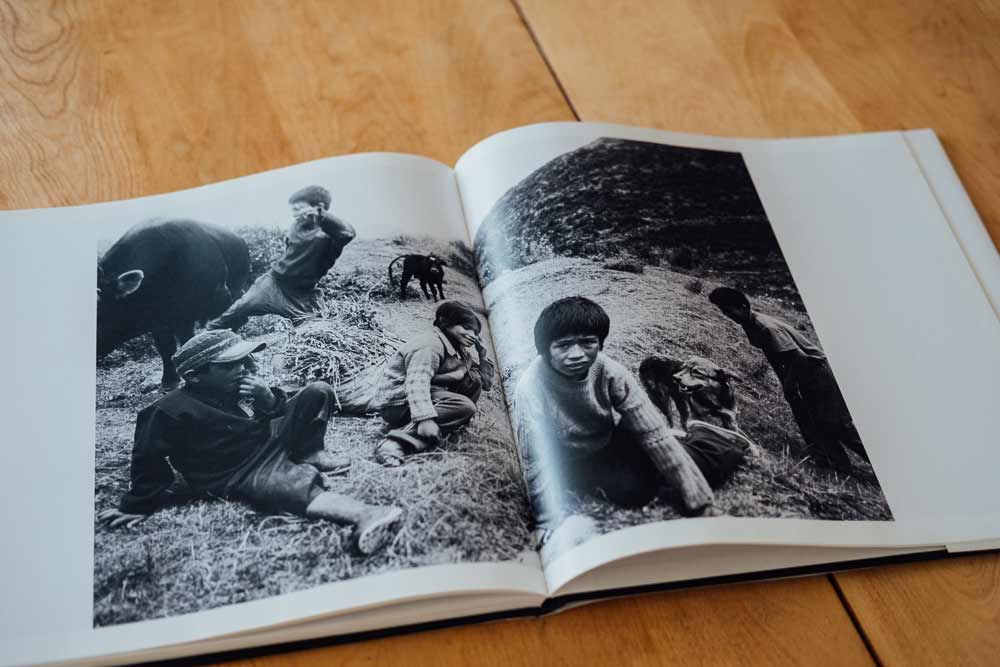

Many of the color images in this particular book were made with 6×6 cameras, so the square format book really fit with my negatives. But I was also using a pair of Leica Rangefinder cameras loaded with black and white film. I knew I wanted many of these photographs to run across both pages to break up the monotony of the color images.

This book was also made for two different groups of people: First, for students. I was teaching in Peru, so I wanted to create a book of my work so that future students would be able to see where we went and what we saw. Second, for the people who helped me while I was in Peru. It’s incredibly important to give back, and a book is a great way to do that. When someone sees what their help resulted in, or sees themselves in a book and that they’re part of a larger conversation, it’s a great thing. And it helps when you return. I could have gone with a 7×7, but the 12×12 has more impact.

How can digital creatives make print work for them? What purpose do print pieces like a book serve in the digital content world?

This is a very important question, and one that I love answering. Yes, we live in a digital world, but that digital world is often times a phony, artificial world of noise and sub-par work being praised as something new or original. The digital world has become about following, and building a following doesn’t always have much to do with making great work.

Print cuts through the noise based on one critical idea: curation. When a creative goes to print, it means they’ve put critical thought toward their work. What are the absolute best images? What’s the cover image? What’s my sequence? How do I best tell this story?

Let’s say you’re an art director or agent looking at thousands of images a day on Instagram, spending perhaps 1.5 seconds on each. Then suddenly, a printed photo book arrives. It’s a total of eight, well-edited, well-sequenced images, placed in a beautiful layout. The creative is basically saying to the client “This is all you need to see and know to understand who I am as a photographer.” I’ve sent portfolio books that are still in those offices five years later. Print is a statement you can’t make on the screen.

When you were a small child, what did you want to be when you grew up? How does what you’re doing now compare?

Like most kids, I went through a range of ideas. When we moved to Wyoming in the mid 1970’s I remember telling the driver of the big rig that drove our belongings out west, that I wanted to be a truck driver. I also remember that man saying, “You know, you might want to rethink that.” Wyoming changed my life, though. I knew that whatever I did in life had to revolve around open spaces.

At the same time, I felt an almost overwhelming need to record things. I kept notebooks, wrote short stories, and asked for my first camera while I was still in elementary school. I didn’t know what journalism was at the time, but my grandfather was a newspaperman for forty years, so it was in my blood. My first written assignment for a newspaper was a bomb threat. When I left to cover it, the assignment editor said, “We don’t have a photographer, so you’re going to have to write and shoot.” Once I had that camera in my hand and a press credential around my neck, I was hooked.

What I do now has changed dramatically, but that boy is still in there. The need for open space has returned with a vengeance. I also still carry a notebook, still write short stories, and still make pictures on a regular basis.

What are the best parts of your job? What are some of the challenges?

There really are no bad parts of my job. There are parts I complain about, but then catch myself and think, “You’re the luckiest man alive.” My job is great for a variety of reasons, most of which are based on the people I work with, the platform behind me, and the fact that Blurb allows other people to tell their stories, just as I do. Humans and the narrative story have a deep connection, going back to the first days of our species. What we’re doing now is only a refinement of this critical experience.

As for challenges, they’re self-inflicted. My biggest hurdle is lack of time. Making great photographs is incredibly difficult and requires two things in abundance; time and access.

What’s one project you’re dying to do?

I keep a list of story ideas that grows each year. I’ll never get to all of them but there are certain things, certain places, that jump out at me. I used to spend all my time thinking about foreign travel. I thought I had to go somewhere exotic to make extraordinary images, but this is simply not true. There are so many places in the United States I’ve not yet seen, and there are so many stories that haven’t been told. I’m in love with the American West, and the Southwest in particular. I could easily spend the rest of my “usable” years behind the wheel of my pickup, exploring the dusty wilds of what’s left of the American West. This one place, this one story, is representative of the entire globe. And it’s right here in my backyard. Migration, the environment, conflict, race, industry, population growth, and art are just a few global stories I can tell by walking out my back door. This is something I literally think about every single day. I’m possessed by the idea. I’m not sure I’ll ever get the chance to really begin, so I attempt “micro-stories” in the meantime.

As someone who works creatively every day, how do you stay inspired and motivated?

I’ve never not been inspired or motivated. Making a single great image, writing a single great sentence, or recording a single great piece of sound is enough motivation for ten lifetimes. Watch a sunrise. Listen to a great piece of jazz. Eat something delicious. Swim in the ocean. Climb a mountain. My problem is my inspiration and motivation make me think about crazy ideas like riding my bike the length of the Americas. Or going off grid with my Leica and spending the next five years hitchhiking around The West making pictures. But let me explain my foundation. Social media lovers cover your ears.

Roughly four years ago, I deleted almost all of my social media. I also made a decision to limit my time online. (A truly epic decision that changed my life for the better.) So instead of social media and the Internet, I read. A lot. I’ve read 150 books over the past two years, which has helped broaden and deepen my knowledge of things I find important.

I also spend as much time as possible outdoors. I do yoga every day, and I continue to learn new things. Guitar, painting, design, Spanish, etc. Doing these things has rewired my brain to consume more in-depth information. I find that when I’m more knowledgeable about a certain topic, it makes me want to embrace it even more.

***

What drives your book design and layout decisions? Get started on your own layflat photo book.

This post doesn't have any comment. Be the first one!